A great product strategy is the foundation of a great product, but a bad product strategy can lead you astray. Product strategies are guides to the future based on the information that you have at the time. They are living documents; as things change and more information comes to light, they should be revisited, revised, and added upon.

This document is a guide for how to build a product strategy.

Section 1 – Understand the Problem

Every product strategy starts with a clear and cogent problem statement.

- Know what problem you want to solve and for whom.

- Identify the opportunity and size it.

I often hear Product Managers say that the problem is winning more customers or beating a competitor. That is not why we build products. We are solving real needs in the world, and a product strategy should reflect that.

Define the problem: What problem are you trying to solve?

Think of your favorite product. Then think of the unique problem it is trying to solve in 10 words or less. Some of the following examples are the company’s mission statement, but not all of them. The most important thing is that the problem is clear.

- Airbnb: Connecting travelers with unique places to stay

- Amazon: Find anything to buy online at a good price

- Coursera: Accessible quality online education for everyone

- Facebook: Connecting with friends and family about things you care about

- Google: Organizing the world’s information

- WhatsApp: Private messaging for low connectivity environments

- YouTube: Sharing videos and finding an audience

You should define the problem in a way that’s unambiguous as to what you are trying to do. A strong problem statement demarcates what you care about, but also what you don’t want to invest in.

Define your audience: Who are you solving the problem for?

Blackberry made a great product appealing to both IT professionals with security and consumers on mobile email. But when consumers moved to other smartphones, Blackberry thought their strength with IT departments would keep them in enterprises. In the end, consumer preference won out.

Ad agencies create ads not to sell products to consumers, but to sell ads to executives who in turn need to believe that these ads will sell products. Knowing whose problem you are solving, and who is deciding if you get to solve the problem is an important distinction. In consumer products, they are often the same person, but in enterprise products, they are often entirely different.

Once you know your audience, segment the market and know who your primary and secondary segments are. It will help you know who you are not serving. Choosing who you will not serve is just as important as knowing who you plan to serve. Eventually, you can choose to expand but start with a beachhead and a place you are likely to win.

Think about a few products and what audience they started with and where they are now:

- Amazon: Booklovers

- Facebook: College students

- PayPal: eBay sellers and small online sites

- QuickBooks: Small businesses

- Snapchat: Teens in western countries on iOS

Having a clear audience means you can focus your efforts on their needs first, and then expand from there. Before you build for the world, win in one market. You can later take the capabilities you built and move to adjacent verticals or experiences.

Understand the market: What is the competitive landscape?

Understanding where you stand and what the opportunity can be is critical to a good product strategy. Defining the overall market, and then breaking down the segments help you see who else is in your space. It also helps you see if it is a prize worth winning. Assessing the market is important, so here are elements you should include:

- Segments – define based on behavioral or needs based on segments

- Market size – opportunity size, number of potential customers

- Competitors – leaders in the space, the concentration of competitive strength

Having a clear understanding of the market today and where it is going in the future will help you understand your position as you build out your strategy.

Section 2 – Identify your unique value

Every company brings something different to the table when solving a problem. Understanding and using those strategic assets is what makes your approach unique. For larger companies, it could be scale, organic behavior, or industry relationships. For startups, it may be nimbleness or focus.

Think about some companies and what they bring to a new business:

- Amazon AWS: Computation capabilities at scale

- Apple iPhone: Human-centric design

- Facebook Marketplace: Buy & Sell Groups and profile selling

- PayPal Merchant Services: Fraud and risk management for small sellers

- Uber Eats: Millions of drivers on the road with an installed base of consumers

Identify your unique assets and how they can give you the “right to win” a specific space. Understanding the best way to leverage these assets helps you build out a credible plan.

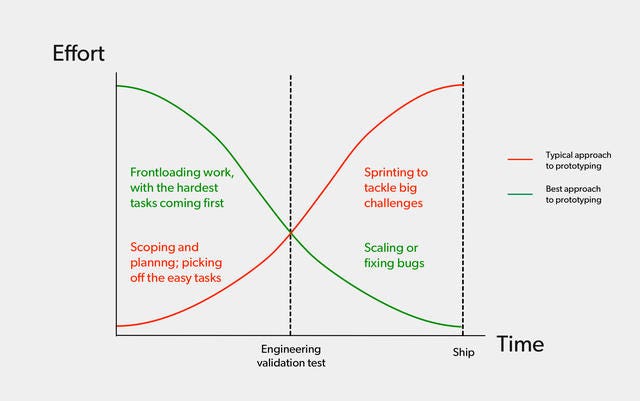

Section 3 – Outline how you will execute

I once worked in strategic consulting. We wrote detailed strategies to help companies win a specific market. But more often than not, we left the engagements knowing the companies could not execute against them. Even if they had the advantage they often lacked the ability to build what we defined.

This is the unsexy truth. Strategy is easy, execution is hard. Many companies have similar strategies, but what separates those who win from those who don’t is execution.

I worked at eBay over a decade ago and at a reunion dinner, we joked that back then, we were all newly minted MBAs at a tech company run by MBAs. The problem was that we spent a lot of time talking about the strategy, but the strategy is only as good as your ability to actually make it happen. I knew it was time to leave when we had just completed a two-year investment in a new checkout system, and we were road-mapping yet another rewrite. When I realized this next project would take nearly three years to build, I decided to leave. I joined Facebook, and in those same three years, I built two different billion-dollar businesses.

A strong roadmap is clear — and not just over the short term but the long term. Two-year roadmaps are not four six-month roadmaps attached to one another. Be clear where you want to be in two years, and then break it down into workable units. Know what you are learning in each six-month phase which will inform the next six months. You should be able to connect the dots between what you do today and where you want to be in two years and then five.

Define success: What does winning look like?

If you are successful, what does your product look like in two years and then five years? Confirm it is achievable and a prize worth winning. Understand what will change in the macro conditions if you do win. Define success as something measurable so that you continuously monitor if you are on your way there.

Identify risks: What are the pitfalls?

In any execution there are risks. Having a clear risk and pre-mortem for your strategy ensures people know you thought through the potential downsides and have plans to mitigate them. Confidence is built through assessment and clear thinking in the face of adversity, not by hiding from potential headwinds.

What a Great Product Strategy Looks Like

When you read a clear product strategy all of the pieces come together like a symphony. From the first notes to the last words the strategy feels complete and actionable.

Here are the four O’s of what I look for in product strategies from my teams:

- Opinionated: A point of view about why this strategy is unique is important. Choosing a perspective and an audience to start with is hard, but it also defines the first phase of learning. A strong strategy makes hard calls and clearly explains them.

- Objective: Clearly outlining opportunity and risks in equal measure is important. Often we want to sell the upside case, but understanding and outlining the risks builds confidence and ensures that you’ve thought about mitigation.

- Operable: A product strategy needs to be doable without expecting lightning in a bottle. The perfect strategy that is not executable is no better than having no strategy at all. I have seen strategies that assume a series of favorable events to line up so that there is little to no chance of success.

- Obvious: The last test of a great strategy is how you feel after reading it. I recently shared a new strategy with my team which took me months of selling to get executive alignment. One of the first questions I was asked by an engineer was, “This is so obvious. Why didn’t we do this years ago?” The right strategy at the right time will often feel obvious, and if it doesn’t you should ask why the organization or the world was not yet ready for it and what it would take to prepare them.

A product strategy is a living document that is written at a moment in time but evolves as you build. It is your north star and your compass all in one. Having clarity of thought at the outset ensures you are leading in the right direction.

This article was originally posted on Substack. Subscribe to Deb Liu’s Perspectives here.